Cogitationes Privatae: My Philosophical Journey or Discours de la méthode

In Cogitatio I, which is part of the first meditation of Cogitationes Privatae written for the dialogues in the Harvard course, the author delves into a personal and intellectual journey that spans a decade of reflection on the history of philosophy, its implications, and its intersections with contemporary conflicts. The narrative begins with a recollection of Samuel Huntington’s theory and the philosophical questions that preoccupied the author’s youth. Guided by a keen sense of plurality in philosophical truths, the text explores how each system of thought proposes its own standards of value, each implying a “God” as the highest reference point for discerning good and evil. The author describes a formative period, where philosophical study seemed like witnessing a cosmic drama—a series of metaphysical conflicts between competing ideals. This sense of conflict, deeply connected to global political and cultural clashes, prompts a reconsideration of philosophy not merely as a pursuit of ultimate truths about Substance or Mind, but as an exploration of its own historical evolution and its resulting “systems of beliefs”. The journey leads to a recognition of the dangers of seeking ideological refuge too hastily, prompting a turn toward ancient philosophy. Here, the author introduces the metaphor of the “primeval continent,” an untouched intellectual landscape that still holds the potential for discovery and reinterpretation. This final reflection signifies a return to ancient wisdom, perceived not as a nostalgic escape, but as a source of philosophical renewal and insight. This work invites the reader to explore not only the vast conflicts within the history of ideas but also the potential for reimagining ancient frameworks in a modern context, where plural truths coexist in a dynamic and often contentious global order.

METAPHYSICSTHEORETICALSIMONE MAO INTRODUCTION

Ten years ago, I was familiar with the core ideas of Samuel Huntington’s famous book—it was quite popular at the time—but I didn’t attach much significance to it.

The history of philosophy had long occupied all my attention. I read through the works gradually, but such a progression formed a genealogical map that frightened and dominated my juvenile period. Each philosophy asserts a form of truth. I saw the history of philosophy as a sequence of plural truths. According to Plato, “One is Good.”* Every philosophical system carries its own standards of value judgment, and these values imply or require a “God” to represent the highest value, by which we can discern what is good and what is not. Thus, this sequence of plural truths is also a sequence of plural values, going side by side. In the same way, logic is identical to ethics.

This fear governed me during the long period from age 16 to 20: studying the entire history of philosophy felt like watching a cosmic drama of battles between gods, whether in ontology or ethics. I knew well that these questions were deeply connected to the conflicts in the world today. Just as Benjamin Barber wrote, “Jihad is, I recognize, a strong term. In its mildest form, it betokens religious struggle on behalf of faith, a kind of Islamic zeal. In its strongest political manifestation, it means bloody holy war on behalf of partisan identity that is metaphysically defined and fanatically defended.” Across the globe, two people, from different regions, hold vastly divergent beliefs and ethics, inherited from the remnants of ancient gods. But nothing in reality is as diverse and conflicting than the history of philosophy, nor as assertive in its claims to truth. I came to see different forms of philosophy as “systems of beliefs”, and in doing so, the history of philosophy itself became an object to be examined.

I no longer felt I should focus, like modern philosophers, on Substance or Mind as the primary objects of philosophy. Instead, I should step outside all these “systems of beliefs” and place the unique phenomenon of the history of philosophy into philosophical examination. I came to realize that today’s global landscape, in a sense, reflects this phenomenon, with the chronological development of philosophical ideas being transferred into spatial conflicts within the world order.

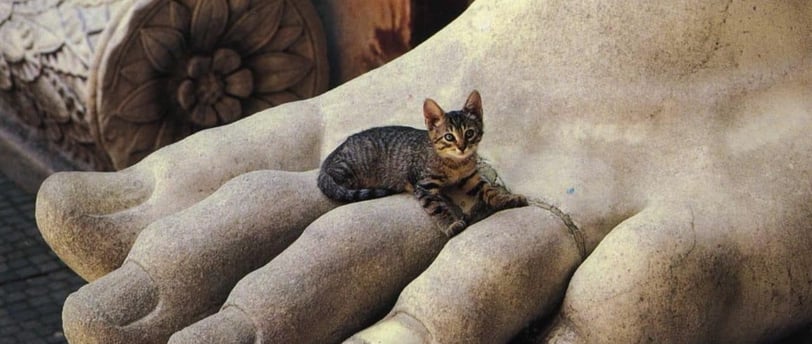

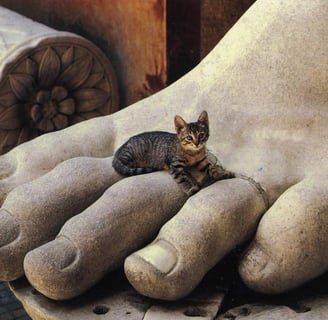

I felt as if I were searching for shelter amid the intervals of these wars, trying to jump onto a “clear” new continent untainted by them. But I soon realized that the haste in seeking such a shelter may conceal a trap of even greater intellectual dangers. These meditations made me anxious and melancholic until one day they finally erupted and changed my entire external environment. These reflections compelled me to seek ancient wisdom, using a term that may seem inappropriate in the eyes of classical scholars, but one I personally like: the “primeval continent”. Ancient philosophy, like virgin land, still holds the potential to be rediscovered and reinterpreted.

Copyright © 2024 Simone Mao. All rights reserved.

Note to Common Readers:

*: In Plato’s philosophy, the phrase “One is Good” can be interpreted as an allusion to the concept of τὸ ἕν (to hen), which translates to "the One." This notion reflects Plato's metaphysical framework, particularly in the context of the Republic and the Philebus, where he associates the One with the ultimate principle of the Good (τὸ ἀγαθόν, to agathon). In this framework, the Good transcends and unifies all multiplicity, serving as the highest principle and the source of truth, order, and intelligibility in the cosmos. The Good is not merely one value among others but the standard against which all other forms are measured.

Plato’s identification of the One with the Good suggests an ontological unity at the heart of all existence, wherein all forms of being find their coherence and purpose. In this sense, the Good represents both the ultimate reality and the highest ethical aim, integrating ontology and ethics in a harmonious unity. Thus, when interpreting “One is Good,” we are drawn into Plato’s vision of an ordered cosmos, governed by a transcendent principle that both defines and grounds reality and guides human life towards its highest fulfillment.

Works Cited

Barber, Benjamin R. Jihad vs. Mcworld: How Globalism and Tribalism Are Reshaping the World. Ballantines Books, 1996.